Use Immer to Manage Your Immutable React State

May 30th, 2020

🍺 🍺 🍺 9 min readIf you’ve worked with React, or frankly any JavaScript framework, you’ve probably come across the idea of keeping state “immutable”. In other words, when working with state, you want to avoid mutating the state object when modifying a particular value. Immutability is a core concept of both object-oriented and functional programming, so before I dive into the awesomeness of Immer, I just want to take a brief moment to expound upon what immutability is and why it’s important in the applications we build.

What is “immutability”?

The root of what it means to be immutable, regardless of programmatic context, is to be unchangeable. Basically, what’s done is done, there’s no going back. Where the textbook definition and programmatic definition differ is that it isn’t a matter of can you, rather, should you?

Because my knowledge of programming is very much limited to the web domain, any further discussion of immutable programming practices will be framed in the context of JavaScript.

I think a common misconception of what mutating something in JS is, is reassigning an already declared variable. For example:

let name = "Bob"

let age = 24

name = age //hey you mutated the name variable!However, this is incorrect because mutability deals strictly with the object primitive type, and therefore reassigning

name to age is not a mutation. As a side note, if this is a behavior you’d like to prevent, either consider using

TypeScript, assigning name as const, or both (my preference).

React promotes immutable state interactions

If you’ve worked with React at all, you likely already know that the framework is an advocate for and adopter of immutability. The documentation discusses this further, but I can give you the TL;DR. The ultimate goal of a JS framework like React is to be “reactive”. In other words, when a JavaScript value changes, react to it! This can be changing a button color, a numerical value, or perhaps an item within a list of items. Let’s take this state structure as an example:

state = {

name: "Bob",

age: 24,

hobbies: ["swimming", "hiking"],

background: {

jobs: ["mechanic", "bank teller"],

},

}If you wanted to add a hobby for Bob, given this structure, you could just push to his hobbies array:

state.hobbies.push("reading")The downside to this approach, however, is that you have no way of knowing which specific properties have changed in that state object since the previous copy of that object was overwritten. This is what happens when you drill down into an object to update a property without caring about other properties of that object.

The modern hooks era has certainly changed the way we handle state in our React apps. Most notably, we no longer have to store all of our

component’s state in a giant object. The useState hook allows us to itemize our state objects within a given component. If you’re like me,

I’m very keen on grouping related component state together within a useState hook. In other words, I often use multiple useState hooks to deal with

objects rather than singular values.

Here’s a look at one of my most common approaches to updating state for a given state object defined within a useState hook:

const initialFormState = {

email: "",

password: "",

valid: false,

}

function Form() {

const [form, setForm] = useState(initialFormState)

//when updating the password field

setForm(prevState => ({ ...prevState, password: "password123" }))

}Any time I update a value in that state object, I have to be sure not to mutate the object as a whole.

The initial argument provided to the second of two values returned from useState is the previous state based on the value(s) passed as argument(s).

This isn’t that bad, right? Pretty clean cut, fairly readable if you’re familiar with arrow functions, implicit returns and object spreading, but this

is the simplest of cases. What if, instead of a form, we’re dealing with an array of user objects like so:

const [users, setUsers] = useState([

{ id: 1, name: "Bob", age: 24, emailConfirmed: false },

{ id: 2, name: "Sarah", age: 30, emailConfirmed: true },

{ id: 3, name: "Kevin", age: 20, emailConfirmed: false },

])And when a user confirms their email, we want to update the emailConfirmed property for their user object.

//confirmedUserId derived from email confirmation

setUsers(prevState => prevState.map(user => (user.id === confirmedUserId ? { ...user, emailConfirmed: true } : user)))So when mapping over the previous user state, when we find the user with an id equal to the confirmedUserId, we want to spread over that object and

update their emailConfirmed property. Again, not crazy, but you can see how this can become cumbersome the more nested your state gets and more generally

the more complex your app becomes.

Immer is here to help

I know, it took me a second to get to Immer, but I wanted to set the scene for why I like to use it. Immer has grown increasingly popular

in the React space over the last couple of years. It operates on a copy-on-write paradigm, which

basically just means it’s able to create a draft copy of state and for any modifications made to that copy, a new state will be published based on those modifications.

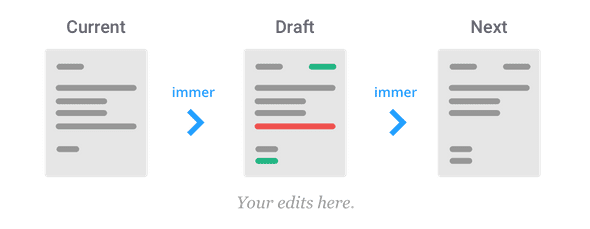

I’m going to steal an illustration from the Immer documentation because I can’t think of a better visualization of this process:

So the crux of Immer is its produce function that accepts your original state copy as an argument and then a callback with a drafted version of that state.

Within this callback, you’re able to hack and slash the drafted copy anyway you like and Immer will be sure that the end result stays immutable. Pretty

cool, right? I think so. Let’s look at how we’d go about updating a user’s emailConfirmed property using produce:

import produce from "immer"

const updateUsers = (state, confirmedUserId) => {

//users will be user state defined above

return produce(state, draft => {

draft[draft.findIndex(({ id }) => id === confirmedUserId)].emailConfirmed = true

})

}And within some click handler we’d make use of this producer like so:

onClick={() => setUsers(prev => updateUsers(prev, user.id))}And just like that we’re able to be much more direct with our state update and, from our perspective, mutate the target user’s object (even though Immer

has our back in this regard). This is a bit clunky, in my opinion, though. Another way we could achieve the same effect and be bit more concise is by writing

a curried producer. I won’t go into what currying is in JavaScript, but basically a curried producer will

only require a state to produce a new value from and any additional arguments relating to the operation. A curried version of updateUsers defined above would be:

const updateUsers = produce((draft, confirmedUserId) => {

draft[draft.findIndex(({ id }) => id === confirmedUserId)].emailConfirmed = true

})Note the signature difference between a regular and curried producer:

//regular: produce(state, recipe) => nextState

//currying: produce(recipe) => state => nextStateThis can be nice if you want to extract functions outside of components for unit-testing, but I personally don’t use this approach very often. There is

a package called use-immer created and maintained my the author of Immer, which provides a useImmer (and useImmerReducer)

hook that allows you to work with your component state the same way you would with useState. So, replicating our initial approach to updating the users array

with useImmer would look something like this:

import { useImmer } from "use-immer"

const [users, setUsers] = useImmer([

{ id: 1, name: "Bob", age: 24, emailConfirmed: false },

{ id: 2, name: "Sarah", age: 30, emailConfirmed: true },

{ id: 3, name: "Kevin", age: 20, emailConfirmed: false },

])

//when updating a user

setUsers(draft => {

draft[draft.findIndex(({ id }) => id === confirmedUserId)].emailConfirmed = true

})Personally, I like to name the values returned from this hook different from how I would with a regular useState hook just to distinguish the two. Also,

with this hook I no longer feel the need to itemize/group state as much seeing as regardless of how nested out state object becomes, updating it will be

relatively trivial with Immer.

Patches

Immer also allows you to track incremental changes to your state with patches. Not every state object will

need this, of course, but for some use cases this can be pretty convenient, specifically if you desire having undo/redo functionality. This doesn’t necessarily

relate to immutability, but I think it’s a pretty neat opt-in feature of Immer. Here’s a brief example of how patches could be incorporated in the above state

set up using Immer’s produceWithPatches. Keep in mind you’d have to restructure the function a bit to handle the tuple that it returns:

Note: in attempts to keep the bundle as small as possible, Immer disables patches by default. If you wish to enable them, call Immer’s enablePatches() method at the root of your app

import { produceWithPatches } from "immer"

const [nextState, patches, inversePatches] = produceWithPatches((draft, confirmedUserId) => {

draft[draft.findIndex(({ id }) => id === confirmedUserId)].emailConfirmed = true

})Here, our nextState would be the updated state object, patches would be an itemized list of changes that were applied to the state, which would look something like

this if Kevin’s emailConfirmed property was updated:

{

op: 'replace', //operations

path: [2, 'emailConfirmed'], //[index of updated value, property that was updated]

value: true, //updated value

}and inversePatches would be a function that would do exactly that — undo all the changes contained in patches. Pretty neat, right? I think so, at least.

Check out this sandbox if you want to play around with produceWithPatches.

My favorite part about Immer is how little it does. It provides such a minimal API and it’s quite easy to go from 0 knowledge to up and running after just breezing through the documentation. It has definitely made my development experience in React a lot more pleasant and I hope that after this you’d be willing to give it a try! Unless you like handling immutability yourself ;)

Thanks for listening 👋🏻